- - - - - - - - - - - -

1) O mně / About me

2) Tvorba / Work

3) Kontakt / Contact

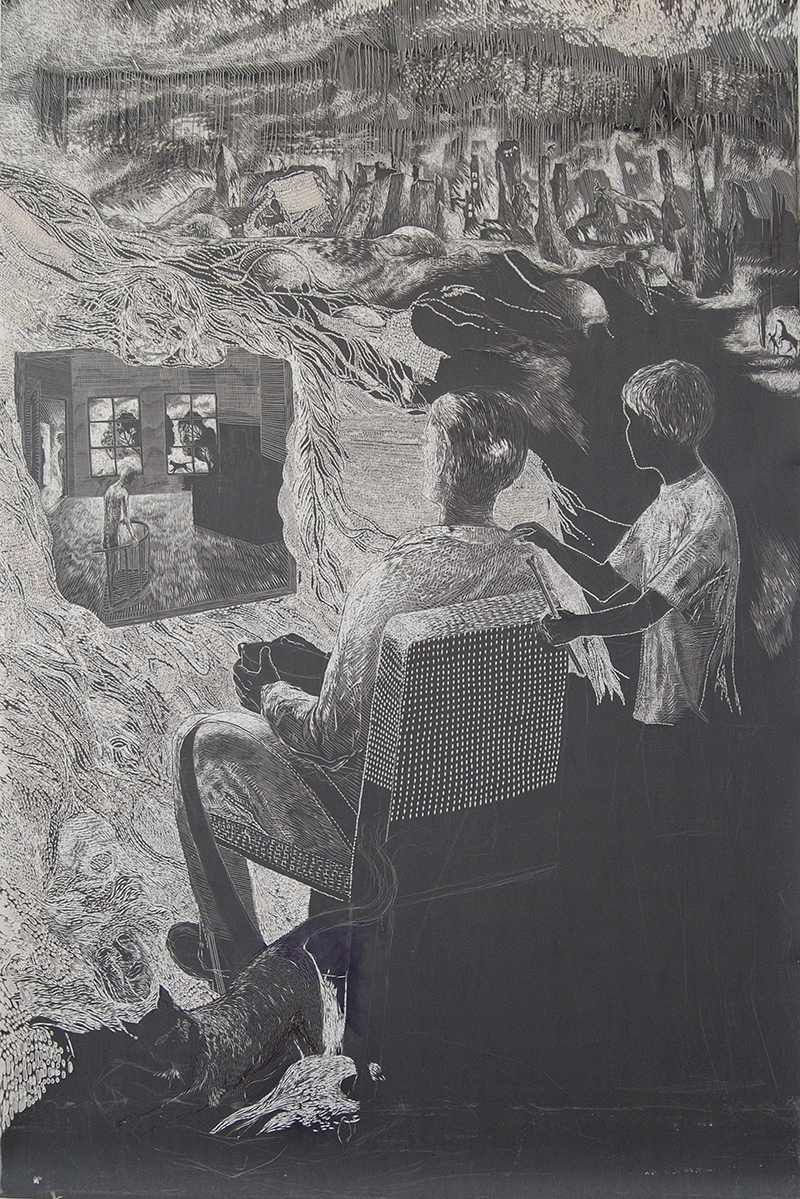

Leží Jano zabitý rozmarýnou prikrytý, relief do PVC, 190 x 300 cm, 2014

/Jano Lies Spread on the Ground, Rosemary Flower is His Shroud, PVC relief

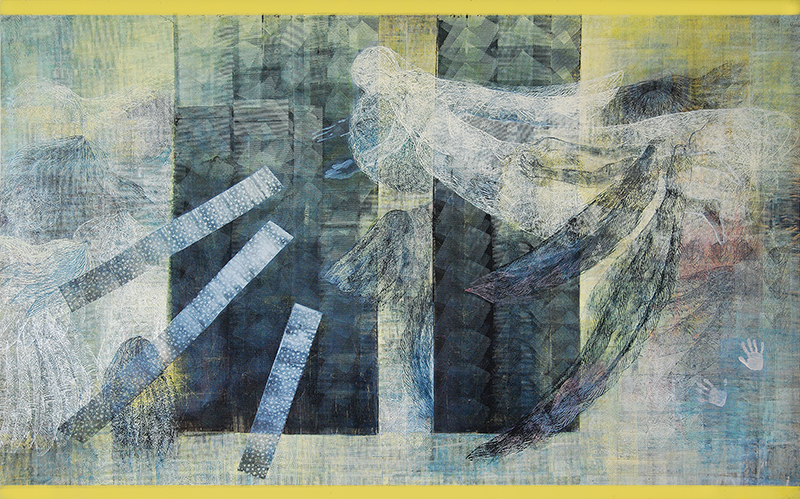

Houpačka, dřevořez, 250 x 400 cm, 2014 / Swing, woodcut

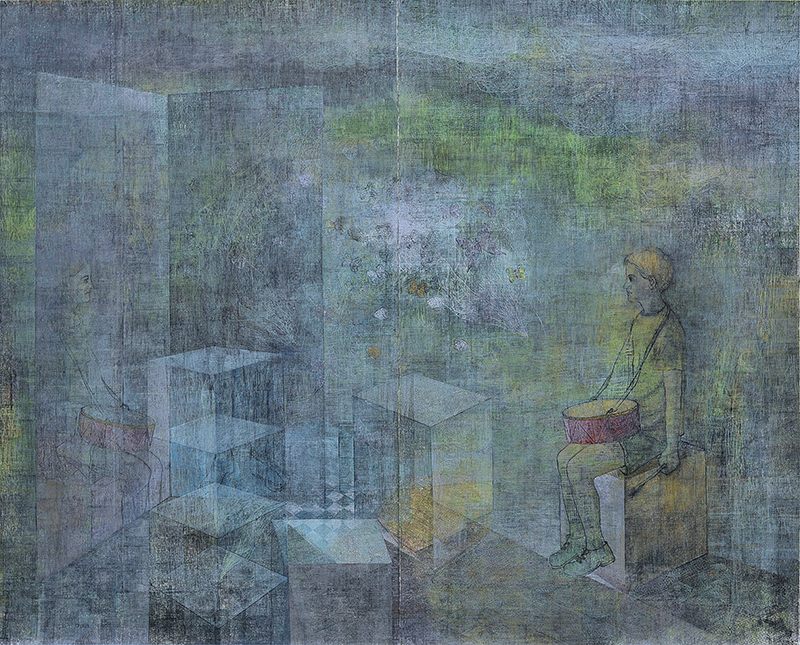

Bubeník, linoryt, 200 x 246 cm, 2013 / Drummer, linocut

Chlapec a obraz, linoryt, 250 x 240 cm, 2013 / Boy and Picture, linocut

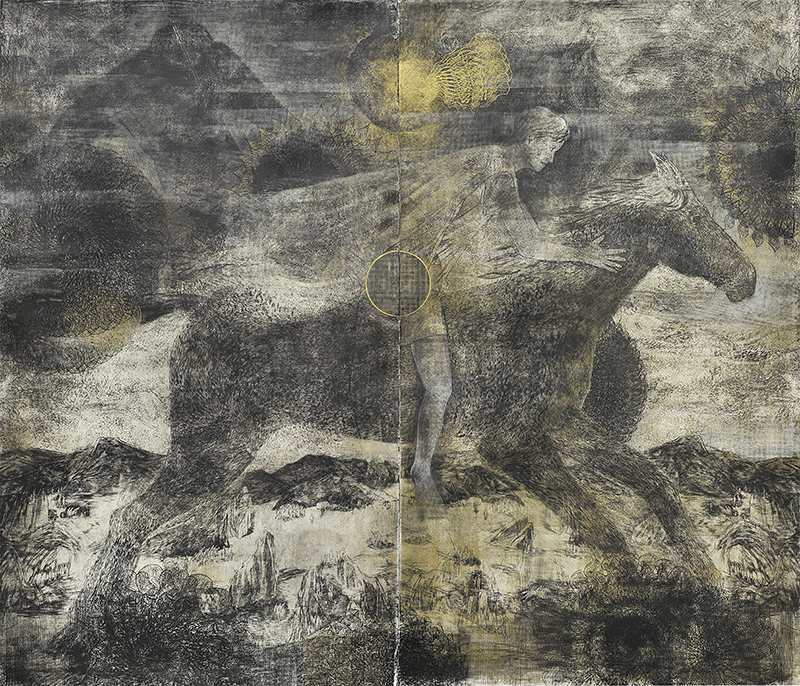

Jezdec, linoryt, 215 x 246 cm, 2014 / Rider, linocut

Dva andělé a dítě, linoryt, 180 x 288 cm, 2007 / Two Angels and Child, linocut

Tři muži a Alexander, reliéf do PVC, 200 x 130 cm, 2016 / Three men with Alexander, PVC relief

Chtěl jsem být generál, ale válka byla krátká

„Chtěl jsem být generál, ale válka byla příliš krátká.“

Tato slova říká v Deníku Jana Vičara „Opa“, česky děda, vlastním jménem Josef K., jinak bývalý příslušník SS policie, který dnes žije se svou dcerou v Kostnici. Jan Vičar se o něj staral jako pečovatel v dubnu 2012.

Z pobytu v Německu si umělec odnesl nejen zážitky, ale i deník se zápisky a kresbami, které přenesl do svého dalšího díla — monumentálních linorytů, inspirovaných životem Josefa K. Obsah linorytů je plný metafor a navazuje na Vičarovy starší práce. Tisk Chlapec s obrazem je inspirovaný lidovou písní Pasol Jano tri voly. Hlavní postavou je tu chlapec s bubínkem, který má ruce na skle a dívá se přes ně na obraz

umírajícího Jana.

Bubínek, symbol dětských her na vojáčky, provází chlapce i v dalších dvou velkoformátových linorytech: V Houpačce a Bubeníkovi. Houpačka chlapce vynáší mimo prostor a čas, umožňuje mu přechod z pevné země do prázdna a zároveň skok do vody pod sebou. Motiv přechodu z jednoho světa do druhého je pak naplno rozvinut v obraze Převozníci (Hotel Melencolia).

U Převozníků se Vičar nechal inspirovat Dürerovou rytinou Melancholie I, která pomocí různých znaků a číslic odkazuje k planetě Saturn, symbolizující plynutí času, smrt a záhubu. Na Vičarově listu je vyobrazen žebřík, který nechybí ani u Dürera. Může to být Jákobův žebřík, přechod mezi nebem a zemí, brána k Bohu a cesta, po které v Jákobově snu sestupovali a zase stoupali Boží poslové. Z tohoto místa k Jákobovi promluvil Bůh. Převozníky obklopují ze všech stran kruhová tělesa připomínající černá slunce, která jsou spojována s árijskými kulty a rozvojem nacismu. Velký sluneční kotouč se však nachází i na hradě Wewelsburg, který nechal rekonstruovat šéf gestapa Heinrich Himmler. 31. 3. 1945 byla část hradu na Himmlerův příkaz zničena a sídlo se stalo na několik desetiletí symbolem zkázy.

Dědovo jméno Josef K. může vyvolávat asociace s Kafkovým slavným románem Proces, jehož tísnivá atmosféra vyzařuje i z Vičarových zápisků z pobytu v Kostnici. Zatímco románový Josef K. byl souzen za zločin, který mu nebyl nikdy sdělen a jehož si nebyl vědom, ale byl za něj nakonec popraven, současný „Opa“ Josef K. se dobrovolně účastnil největšího vojenského konfliktu minulého století, svého jednání nikdy nelitoval a věří, že mu bude po smrti určeno místo v nebi.

Jan Vičar však starce nesoudí; působí spíš jako svědek, zapisovatel jeho života a rodinných poměrů, jež transformuje do metafor grafik, navazujících na jeho předchozí práce. Figury na Vičarových tiscích jsou bohatě obestřeny ornamentem. Umělcův výtvarný přednes přesahuje hranice grafiky a vstupuje do oblasti malby, jak tomu bylo i v dřívější tvorbě. Vičarova praxe vychází z poučení, jemuž se mu dostalo za dob studií, kdy byl na AVU žákem Františka Hodonského a jeho ateliéru krajinomalby, poté však ještě navštěvoval ateliér grafiky Jiřího Lindovského. Obě média tak dokáže propojit a grafiku, obor většinou drobných formátů, paradoxně monumentalizovat i pomocí malířských technik.

Markéta Odehnalová, 2014

deník Jana Vičara

V lednu roku 2012 jsem byl takřka bez finančních prostředků. Za můj poslední honorář byla zakoupena nová střecha na mém lesním domě. První pracovní příležitost, kterou jsem tehdy objevil, byla práce lyžařského instruktora v Krkonoších. Tato nedlouhá zimní kariéra instruktora se mi líbila i přesto, že jsem měl na starosti korpulentní německé dámy s artrózou a malé děti.

Další možnost byla práce pečovatele v německé Kostnici.

Mým příjezdem do Kostnice v dubnu 2012 se daly věci do pohybu a já jsem v myšlenkách začal pracovat na novém cyklu obrazů. Z každodenních zápisů do skicáku vyplývá, co se v této „rodině“ dělo.

— Jan Vičar , v lese pod Javořicí u Telče 27. 4. 2014

11. 4. Tak Opa je bývalý člen SS policie, jak mi řekla El. První týden byl poznamenán jeho nenávistí. Byl jsem opakovaně nazýván cikánem a čertem, který by se měl vrátit do koncentráku. Stěžoval jsem si jeho dceři El., že za daných okolností nebudu v práci pokračovat.

El. mě prosila a plakala, že nikoho nemají a že vše dělám dobře, jen ať zůstanu. Souhlasil jsem.

El. nemá žádný hezký vztah ke svému muži. Večer, když se potkají, ani se nepozdraví. Neustále si něco vyčítají. Do toho obvykle začne řvát Opa, aby ho vyhodili na ulici, že už nechce být na světě. El. kolem něho létá jako pilná včelka Mája, ráno čerstvý croissant, já pak vařím oběd. Vždy čerstvý, protože jídlo z minulého dne se nesmí jíst.

Večer jsem byl s CH. (manžel El.) na koberečku. Velká šéfka si nás povolala. Byli jsme jako školáci před paní učitelkou. CH. se provinil, že dal Opovi starou rybu (stará nebyla) a já si prý zvykám často odcházet na procházku. Odvětil jsem, že jsem se vždy dovolil a že nejsem zvyklý být ve 40 stupních vedra.

Všichni se tomu zasmáli, kromě El.

12. 4. Dnes jsem to Opovi zavařil, dal jsem mu na snídani velikonočního beránka. Bohužel mu kousek zaskočil a on začal kuckat. Já ho přitom mlátil do zad. El. mě obvinila, že jsem způsobil dědečkovi kašel. Po akci s beránkem El. vyházela hystericky z lednice skoro všechny potraviny. Prý byly staré.

Večer byla ještě scénka se záchodem, který jsem vydrhnul, pač byl od Opy pochcaný. Zapomněl jsem tam ale vodu se saponátem, kterým jsem záchod umýval. El. mě hned obvinila, že se toho napije kocour a že zdechne. Na můj komentář, že se kocour sám od sebe chemie nenapije, začala trousit ironické poznámky.

13. 4. ráno El. se nelíbilo, že jsem nechal po úklidu nádobí pootevřenou skříňku. Opa si stěžoval, že mu padají spoďáry. Až dodatečně, co visely na šnůře, El. zjistila, že mají prasklou gumu. Začala nadávat, že je třicet Euro v prdeli. Já na to, že mi to může strhnout z platu, že jsem to nepoznal. El. řekla, že tedy nemám vykonávat tuto práci, když nepoznám prasklou gumu. Dodal jsem, že jsem gumu nepřekousal a že klidně odejdu, jestli chce.

13. 4. Večer přinesl opět něco, co jsem nečekal. El. se přivalila po šesté a udělala kravál, že Opa málo pil. Má vypít tři velké sklenice dopoledne a čtyři odpoledne. Poctivě jsem dělal čárky za vypité sklenice. Nedá se to do něho na sílu nacpat, tak těch sklenic bylo málo. Za to její štěkání budu dělat čárky i za nedopité sklenice. El. někam zmizela a dědeček se strašně potil. Zhasnul jsem tedy světla, co jsou nad ním a která mu zahřívají hlavu. Syn S. se poprvé osvědčil jako informátor. Pak jsem Opovi rozepnul košili a začal mu s ní pohybovat a takto ho ovívat. El. se dovalila a začala na mě řvát, že prochladne atd. Je tu stále 40 stupňů Celsia. Začala ječet o dalších věcech. Taky o tom, jak jsem dal Opovi toho beránka a že všichni chlapi jsou sráči. Já na to, že jsem slyšel, že to říkala už v noci. Dnes jsem kmital od 6.00 do 16.00, pak jsem si chvilku kreslil Opu, jak spí. S. to zase vykecal. Je to malá svině. Situace vygradovala u snídaně.

CH. špatně nakrájel dědečkovi salám a El. ho proto vyhodila do dřezu. Nakrájela mu ho znovu. Ve 22.00 jsem šel na procházku, nemám povoleno déle, než do 23.00. Je to jediná chvilka klidu za celý den. Vykouřím za tu hodinu asi pět cigaret a procházím se v noci mezi zahradami. Po mém návratu se situace opět vyostřila v další řvaní. Opa má něco s okem a já jsem na vině. Arschloch – díra do prdele, je nejčastější slovo, které slyším. Kolem 11.30 jsem šel spát. Řvaní slyším ještě v 1.30 po půlnoci.

14. 4. ráno Opět řvaní, tentokrát jsem zapomněl při úklidu Jar na kuchyňské lince. Nechal jsem ho tam, protože práce nebyla ještě hotova. Mrskla nádobu pod dřez se slovy, kolikrát to bude ještě uklízet. Hovězí, co jsem včera uvařil s omáčkou, bylo vyhozeno do koše.

Teprve večer jsem se takřka po týdnu dozvěděl, že s námi bydlí ještě dva psi. Už chápu, proč nesmím ani na krok do jejich bytu. Tam to musí vypadat. Ty psy jsem ještě neviděl, že by je někdo venčil. Jsou to podvraťáci, ale s takovou agresivní povahou. Hned začali cenit zuby a jeden mě poškrábal drápama. Je to trochu do krve, protože kvůli vedru nosím kraťasy.

Nejmilejší je ale kocour Romeo, občas mu přilepším něčím z lednice. Je to rezavý kámoš.

15. 4. El. se přivalila ve 21.15. Všichni jsme čekali, až nachystá Opovi talíř. Už si nepamatuji proč, ale lapla svůj talíř s jejími oblíbenými majonézovými saláty a zmizela ve svém bytě. Vrátila se kolem 22.00, v době, kdy jsem chtěl jít na moji hodinovou procházku. El. mě začala úpěnlivě prosit, abych nikam nechodil, protože ve vedlejším bytě je na návštěvě pan B. (majitel domu) a mohl by mě potkat a vidět. Odpověděl jsem, že jsem čistě oblečen (i když bývám nazýván špinavým prasetem) a že absolutně nechápu, proč by mě B. nemohl vidět. Divil se tomu i její manžel CH. Začala štěkat potichu, aby to B. neslyšel. Použila termín Tschechei. Vysvětlil jsem jí, že to je hanlivé označení mojí rodné země, které má původ ve Třetí říši. Znovu řvaní, už nahlas, že jsem český nacionalista. Pak mě pomlouvala u Opy, že jsem alkoholik, protože piju víno. To neví, že mám v autě schovanou flašku slivovice. Vždy si před procházkou dám panáka, abych se trochu uklidnil. Šel jsem ven bez povolení a pana B. jsem nepotkal. Protože jsem neměl klíč, musel jsem zazvonit. Bestie už mě čekala na chodbě.

Skákala snožmo s mírně roztaženýma nohama jako opice a přitom se škrábala na kundě. Do rytmu opičích poskoků řvala: „Tohle je to jediné, co umíte, vy česká prasata.“ Neubránil jsem se výbuchu smíchu.

16. 4. Neděle je můj jediný volný den. Jel jsem do Švýcarska do Schaffhausenu k přátelům. Konečně na pár hodin klid. Večer jsem se musel vrátit. CH. mi byl otevřít bránu na parkoviště. Na můj dotaz, jak se měli, odpověděl: „Sračky, jako vždycky.“ Přišel jsem nahoru a teprve při světle jsem uviděl, že má Opa monokl pod okem a CH. na krku. Nakonec z nich vylezlo, že se u oběda pomlátili. S. prý držel Opu a El. držela CH., prý by se jinak pozabíjeli. Úplně si to dokážu představit. Permanentně na všechny naštvaný CH., který nemůže nikdy nic říct ani rozhodnout, a starý harcovník Opa od Leningradu, kolem kterého létá pilná včelka Mája. Oko za oko, zub za zub, monokl za monokl. CH. v takových chvílích obvykle začne hajlovat, aby nasral Opu. To jsem zažil několikrát.

17. 4. Svině přijela a vše zase špatně. Večeři většinou chystal CH. s mojí pomocí. Čekal jsem do 20.00 a nic se stále nedělo. Tak jsem čekal až do 20.30. Poté mi dodatečně vytkli, že jsem to měl udělat. Řekl jsem jim, že při první příležitosti odejdu, že už toho mám plné zuby. Klíč, který nechávali ve dveřích bytu zevnitř, tam tuto noc nebyl. Jsem de facto zamknut. Okno použít nemohu, jak jsem si myslel, že se spustím po natrhaném prostěradle. Jsou v něm mříže. Při usínání ještě slyším ironické poznámky o tom, jak na chatě v lese, kde bydlím, jím jen špek a zapíjím ho vínem. Ještě mi bylo řečeno, že roleta na okně v obýváku, kde Opa tráví celý den, musí být dole, protože pan B. (majitel domu) nemá rád, když je vytažena a je vidět dovnitř. Nechápu, jak může být vidět dovnitř, když je byt v patře. Rozčilil jsem ji poznámkou, že to tam je jako v bunkru. Stále pokračují ironické poznámky, jestli si pamatuji věci ze včerejška apod. Zakázala mi chodit na balkon, tak jsem si tam byl zakouřit. Večer zase vše špatně. Opa dával pochcaný papírek, kterým si utírá pinďoura, do hajzlu. Spadl mu totiž na rantl hajzlu. Zase poznámky, že to je moje práce uklízet pochcané papírky. Pak jsem vedl Opu do postele. Zase vše špatně, Opa se mohl praštit do hlavy, ale nepraštil. Znovu mi bylo zdůrazněno, že rolety musí zůstat dole, aby dovnitř nebylo vidět. Při

večeři jsem podal špatně vodu nebo jsem použil špatnou sklenici na pivo. Další výtka, dveře na balkon nebyly zamčeny, jenom zaklapnuty. Zapomněl jsem na to. Už se ze mě stává blázen. To je asi smysl toho všeho. Dveře do koupelny jsem zase nechal otevřeny v době, kdy bylo stropní okno otevřeno a na Opu táhlo. Okno ale otevřela ona a zapomněla ho zavřít. El. mi řekla, že na procházku mohu až od 22.00. Už s nimi odmítám večeřet ty majonézové saláty všeho druhu. Řekl jsem jí, že jdu do svého pokoje a ať na mě zařve, když bude něco potřebovat. Ještě mě sjela, že jsem v poledne Opovi sežral oběd. Jídlo jsem mu nesežral, on ho nechtěl. Opa nejí nudle se sýrovou omáčkou. Má totiž rád pravou těžkou českou kuchyni – vepřo–knedlo–zelo.

18. 4. Gestapačka má volno. Ráno mi zasunula pod dveře papírek s úkoly, které mám vykonat. Vytkla mi, že nevytírám podlahu. Odpověděl jsem, že mi nikdo neřekl, jak často čím atd. Vždy jsem umyl hajzl a koupelnu. Tvrdila, že lžu, že mi CH. přístroj ukázal. Já na to, že ne, a tak pořád dokola. Dotáhla červený vysavač, do kterého se dává nádobka s vodou. Zkoušela, jak jsem chytrý, jestli dokážu nádobku zasunout správným směrem. Netuší, že většina akademiků je technicky absolutně nepoznamenána. Já jsem ve zkoušce obstál. Vysavač je šunt, s hadrem a kýblem bych to měl dříve. Opovi jsem nepověsil v jeho místnosti spoďáry, páč jsem ho nechtěl rušit. Spal ještě.

10.20 Opa sám vstal a že chce na hajzl . Tak jsme vyrazili hlemýždím tempem 20 metrů za 20 minut. Nemůže chodit. Má berle. Já stojím za ním nebo před ním, kdyby náhodou padal. Během naší hajzlové procházky se přiřítila svině a že neměl vstávat, že bude mít špatné měření a že jsem lhář. Ječela tak, že z toho byl Opa celý rozrušený a jenom na mě pomrkával, že jako ví, o co jde. Pak jsem si musel vyslechnout ironické poznámky o tom, jestli poznám, až zapípá budík. Jak zapípá, mám odstavit maso, protože ona musí vařit. Já totiž všechno připálím. To se stalo minulou sobotu. Vařil CH. a jídlo připálil. Já jsem dodatečně s jídlem míchal, aby nebylo připáleno ještě více. S. opět všechno vykecal. Svině malá.

Poledne – svině velká se dovalila, další ječení, že jsem neuklidil vysavač. Neuklidil jsem ho proto, že byla mokrá podlaha, kterou jsem nechtěl pošlapat. Problém s ručníky. Až po týdnu mi bylo vysvětleno, kde je jeho ručník a jak se vyměňují. Jednou jsem na to zapomněl. El. vzala ručník na pinďoura a dala mi ho na obličej, odstrčil jsem ji. Jestli si s tím chci utírat ksicht a abych to dělal pořádně, protože do ručníku, do kterého si on utírá penis, ona se utírat nebude. Řekl jsem jí, že já rozhodně také ne a navrhl jsem jednodušší systém výměny ručníků. Zuřila ještě více, když jsem podotkl, že nevím, jestli má penis, že jsem žádný neviděl nebo je tak malý, že ani vidět není. Zuřila. Jídlo jsem mu nedal, protože ho nechtěl a dodal jsem, že je zdravé na jaře dva dny nejíst. Ihned se to obrátilo proti mně. Nazvala mě sráčem. Já jsem se oblékl a šel na 15 minut ven během jejich oběda. Zakázala mi večer jít na hodinu ven. Odpoledne se bestie nějak změnila. Byla jako mílius, smála se, dokonce i na mě.

19. 4. Dnes ráno taky vše O.K. Hmmm.

15.30 přišel S. a hned volalo gestapo, kolik toho Opa vypil. Jsem opětovně nazván prasetem. Po snídani Opa vypráví o vesnici, kde se narodil, a o svém dětství. Už poněkolikáté rozhovor ukončí slovy: „Chtěl jsem být generál, ale válka byla příliš krátká.“ Raději nic nedodávám a zapínám televizi, kde běží oblíbený seriál Richter Hold. To je také symbolické. Opův nejoblíbenější televizní hrdina je soudce Alexandr Hold.

20. 4. Ráno volala agentura, že gestapačka chce, abych u nich byl ještě 24. 4. Odepsal jsem, že za to chci 250 Euro. Tlustá svině opět řve, že jsem líné prase. Ted řve Opa z hajzlu na El.: „Du bist ein Schwein.“ Nadávky pokračují, situace graduje. Mám ale pevné nervy kupodivu, jinak bych ji už podřízl jako prase. Naše konverzace vypadá asi takto : „Vičááár, smradlavé české prase, nemáte co na práci?“ „Bechéééér, udělám to, až vypadnete.“ To je tedy ráno. Konečně vypadla. Řve ale zase dědek, který má vstávat přesně kvůli měření tlaku, cukru, kyseliny a tepu. Chce ještě spát. Dávám mu velkoryse 10 minut, náckovi jednomu. Vstává, šouráme se na hajzl, po cestě si ho někdy kreslím. Dávám ale na něj pozor. Nejdříve se umyje, vyčistí zuby někdy, převleče se. To děláme pořád, to převlékání. Opa se enormně potí, jako my všichni. Venku praží odpolední slunce a tady se topí naplno. Opa přeci jen trochu promrznul u toho Leningradu. Dám mu naslouchátka, taky je nechce. Při jeho mytí pozoruji někdy jizvy na zádech. To má z českého koncentráku. El. už mě stačila obvinit, že za to můžu. Pak vyrazíme na snídani. Někdy si povídáme u snídaně. Včera mě ale Opa překvapil. Zanotoval s dojetím a slzami v očích českou hymnu, samozřejmě v němčině.

21. 4. Ráno zase řev na všechny. Pak zmizela. Uklidil jsem nádobí, vypral, vyluxoval a vytřel podlahu. Nasnídal jsem se. Pak budím Opu, měřím tlak ještě v klidu, kapu nějakou sračku do očí, měřím kyselinu, cukr. Vše v normálu. Dědek sice nemůže chodit, ale kořínek má tuhý. Včera mi zakázala dávat mu tablety, protože jsem nezodpovědné prase. Dnes to má za úkol CH. nebo S. Jenže ti tu nejsou. Tablety musí včas do náckova břicha, ještě před snídaní. Dávám mu je. Vím přesně kolik a které. Opa sice protestuje, že na mě bude zase řvát, ale co na tom. Při čištění zubů Opa podotkne: „V nebi se mě nikdo nebude ptát, jestli jsem si čistil zuby nebo ne.“ To je fascinující, on si myslí, že se dostane do nebe. Volala svině, jestli tam je CH. nebo S. Odpovídám, že ne. Mile se mě ptá, jestli můžu dát tablety. Odpovídám, že sice nejsem odpovědný, ale že mu je dám. CH. a S. mají průser hahahaha.

Večer dostávám novou přezdívku. Je pravda, že těch prasat už bylo hodně. Jsem nazván Scheisstipem. abych nezapomněl Scheisstipem proto, že si Opa ublinknul. Řekl jsem jí, že jedu v úterý, jak bylo domluveno, a jestli ne, že jdu na policii. Ona na to, že policajtům řekne, že jsem Opu zmlátil, protože má podlitiny na hrudníku. To tam má z minulého týdne, jak se pomlátil s CH.

22. 4. Konečně svoboda ve Švýcarsku. Nejdříve jsme s F. napsali stížnost, pak jsem jel do Steinu, kde jsem se seznámil s buddhistou Andym, mým budoucím zaměstnavatelem. Šli jsme na večeři a poté jsem dovezl L. do Schaffhausenu. Večer jsem měl pohovor s gestapačkou. Krotila se, ale stejně byla protivná. Pořád chce zaplatit andílky z Betlému. Betlém stál ještě v dubnu hned pod dotyčnou roletou, kterou jsem dvakrát aktivně vytáhl. Protože Opa chtěl vidět ven a já jsem nechtěl být ve dne po tmě. Před dvěma dny už byla roleta definitivně stažená, já sedím s Opou u televize, koukáme na soudce Holda a najednou prásk. Celá roleta sama od sebe spadla na Betlém. Rozbili se čtyři andílci. Ve své naivitě jsem je slepil a o všem informoval El. Ta mě okamžitě obvinila, že to je moje vina, protože já jsem s roletou manipuloval.

23. 4. Pondělí. Byla vystavena faktura na 1 600 Euro.Jsem zvědav, co bude večer. Včera volali Bestii z agentury.

Opa na ni řval do telefonu, že je jako v hrobě a že chce vytáhnout roletu. Pak sebou začal mrskat, že si to jako vytáhne sám. Gestapačka na něj řvala do telefonu. Večer jsem byl obviněn, že jsem Opovi rozsypal a nepodal léky. Bylo to proto, že S. našel nějaký prášek na posteli. Před odchodem (o 15 minut dříve), nechtěla mě pustit, tak jsem ji poslal do prdele. Jak jsem došel, vybalila na mě, že ukáže doktorce, jak jsem zmlátil Opu.

24. 4. Problém, technik chce dojet na ty uši pana K., ale svině tady není. Já ho mám odříci. Jsem zvědav, jak to dopadne. Naslouchátka Josefa K. jsou stále nevhodná, technik, co mu je upravuje, sem jede už počtvrté. Já jsem ovšem jedno naslouchadlo mimoděk upustil na zem. Kousek plastu se odštípl, tak to budu asi platit.

Opa dělal pojišťováka ve Schwarzwaldu až po Kostnici. Diecéze Freiburg.

Teď dojel na ty uši. Předtím jsem převlékal Opu, ale pomalu. Tak přiskočila, stáhla mu triko a mrskla mi ho do obličeje. Tak jsem jí ho taky mrsknul do obličeje. Řekla, že jestli ji udeřím, tak je Schluss. Řekl jsem jí, že jí takovou radost neudělám. Večer mi zakázala jít ven, tak jsem šel.

25. 4. ráno Asi budu potřebovat právníka. Malý Angeber (udavač) S. zůstal doma, bolí ho hlava chudáčka. Chtěl jsem si jít na balkon zakouřit, ještě že jsem nešel. S. by to hned nahlásil gestapu. Situace graduje večer. Opovi zaskočil kousek jídla – to si myslela El. Jenom zakašlal. Já jsem ale nazván hovnem. Zjistila, že jsem jí aktivně vysušil v sušičce halenku a rifle. To se asi všechno smrsklo, takže to neobleče. Jenže ona to v sušičce zapomněla. Mojí povinností není kontrolovat její prádlo, prostě to bylo v sušičce, tož jsem to vysušil na teplotu, co se suší generálovi spoďáry. Řve tady jako postřelená svině. Je nepříčetná, když jí řeknu, že má motivaci zhubnout. Kope do dveří a sprostě nadává. Prý mi odečte dalších 150 Euro. Strašně na sebe řvou s Opou. Nedají mu pokoj. Sedím s nimi po večeři. Svině už neví, jak se mi vysmát, tak ironizuje melodii Vltavy od Bedřicha Smetany. Přesně tu část, kde Smetana mistrovsky ztvárňuje zurčící pramen Vltavy. Svině dělá něco na způsob blu, blu, blu. Paroduje bublání vody. Mám chuť jí plivnout do ksichtu. Aspoň jí řeknu, že všechno neduní jako Wagner. Zase na mě vytahuje, jak jsem zmlátil Opu. Ptám se CH.: „CH., vy víte, jak to bylo s Opou a že jste ho zmlátil.“ Odpovídá : „Na nic si už nepamatuji.“ Ptám se ho, proč je s touto strašnou ženskou? CH. se směje poprvé od srdce. Hádáme se o penězích. Nechtějí mi zaplatit velikonoční svátky, za které je ze zákona dvojnásobná mzda. Tvrdí, že jsem nic nedělal. Já tvrdím, že jsem tam byl k dispozici a několikrát jsem se ptal, co mám dělat. Pamatuji si na to, že mi o svátcích říkali, že mohu jít na procházku atd. Nikdo ale jasně neřekl, že mám volno. Je to zbytečná argumentace.

Večer probíhá další hádka, odmítám s ní komunikovat, na Opu už kašlu. Zítra odjíždím. Stále řve, kope mi do dveří. Otevírám dveře, snažím se být slušný, ale moc to nejde. Ona nadává, já jí také. Chci zavřít a zamknout dveře. Vecpala se ale svým tlustým tělem do dveří a tato funící zpocená bestie zapřená mezi futry mi přikládá ostrý pilník na břicho. Praštím ji do ruky, ona vykřikne a pustí dveře. Konečně mohu zamknout.

26. 4. Ráno je klid, svině je pryč. Je tu pouze S., ten mi má zaplatit mzdu. Z celkové částky 1 600 Euro jsou odečteni andílci, blůzka a rifle, oprava naslouchátka. Udavač S. mi vyplácí 1 130,68 Euro. Loučím se s Opou a odcházím z bytu. V chodbě se ke mně přitočí kocour Romeo, kterého jsem měl z celého osazenstva nejraději a kterého jsem měl zakázáno hladit. Míjím fotografii usmívajících se El a S. Mám chuť na fotku plivnout, ale ovládnu se.

Ještě krátce navštívím paní doktorku, která má ordinaci ve stejném domě. Dvakrát jsem ji potkal u „nás“.

Náš rozhovor probíhá přibližně takto:

Jan V.: „Dobrý den, paní doktorko, mohu s Vámi mluvit?“

Dr. O.: „Ano, co si přejete?“

Jan V.: „Pracoval jsem tady v domě u paní El. jako pečovatel. Paní El. mi říkala, že má od Vás doklad o pohmožděninách na těle Josefa K. El. mě také obvinila, že jsem Josefa K. zmlátil.“

Dr. O.: „Několikrát jsem Vás viděla a vím, že jste u paní El. pracoval. O této rodině víme a sledujeme, co se tam děje. Neděláte na mě dojem, že byste mohl zmlátit starého bezmocného muže. Vím, že jste to neudělal.“

Jan V.: „Děkuji Vám.“

Dr. O.: „Prosím a přeji Vám šťastnou cestu.“

Téměř na den přesně, kdy přepisuji deník z Kostnice do počítače, jsem před dvěma lety s rozporuplnými pocity opouštěl Josefa K. a jeho rodinu.

Kdo byli tito zvláštní lidé? Manžel CH., zbabělec a zoufalec, který byl šťasten, když mohl odjet do práce a na pár hodin nevidět El. Člověk, který málokdy mohl něco říct. Člověk, který mi lhal do očí, když tvrdil, že jsem zmlátil generála Josefa K.

Vnuk S. se stal za jeden měsíc nejpilnějším udavačem v Kostnici.

Nejsilnější je ale vzpomínka na El., která nenáviděla všechny kolem sebe. Vidím ji živě v jejích volných domácích zelenkavých šatech, jak zpocená vedrem se s mohutnými prsy naklání nad hrncem s nějakým jelitem nebo vepřovou pečení pro Opu. Nikdy nezapnutá digestoř, málokdy otevřená okna, těžký vzduch, vedro k zalknutí a hrubé urážky, to provází stále mé vzpomínky na tuto rodinu.

Nenaplněné generálské sny Josefa K., jeho stesk po Sudetech, kde prožil svoje dětství, česko–německá vesnice, kde vyrůstal a hrál si jako dítě a kde také viděl první maršparády, bitva u Leningradu a následný český koncentrák v České Kamenici, to vše se v jednom měsíci roku 2012 odrazilo v mojí mysli. Stále mám před očima tohoto smutného generála a jeho touhu. Člověka, který slzel dojetím, když v televizi viděl mašírující německé vojáky v nějakém dokumentárním filmu z druhé světové války.

Byl jsem tehdy rád, že odcházím z toho podivného černého domu, kde se nesměly vytahovat rolety v oknech. Pamatuji si, že svítilo slunce a já jsem odjížděl na jih do Švýcarska k buddhistům, kde jsem měl pracovat na stavbě jejich domu. To už je ale jiná historie.

— v lese pod Javořicí u Telče, 27. 4. 2014

I wanted to be a general, but the war was too short

These are words uttered in Jan Vičar´s Diary by “Opa”, or Grandpa, real name Josef K., an ex-SS police officer who now lives with his daughter in Konstanz, Germany. Jan Vičar looked after him while working as a health-care provider, in April 2012.

Life experience was not all the artist brought back from his stay in Germany; whilst there he also kept a diary containing notes and drawings, which he has incorporated into his subsequent work: a series of monumental linocuts inspired by the life story of Josef K. The content of these linocuts, filled with metaphors, links to Vičar´s previous output. The print Boy with a Picture was inspired by the folk song Pasol Jano tri voly. The key figure here is a boy with a small drum, his hands pressed onto a glass pane through which he peers at a picture of Jan in his death throes.

The small drum, symbolizing children playing soldiers, also accompanies the boy in two other large-scale linocuts, The Swing, and Drummer. Here the swing ejects the boy out of space and time, enabling him to pass from solid land into the void, whilst simultaneously to dive into the water below. The theme of transition from one world to another is developed still further in Ferrymen (Hotel Melencolia).

For Ferrymen, Vičar drew inspiration from Dürer´s engraving Melancolia I, wherein various symbols and figures are employed with reference to the planet Saturn, symbolizing the flow of time, death and ruin. Vičar´s sheet features the depiction of a ladder, which is also present in Dürer´s print.

It could be Jacob´s Ladder, marking the transition between Heaven and Earth, the gateway to God, and the staircase descended and ascended in Jacob´s dream by God´s messengers. It was from here that God spoke to Jacob. The ferrymen are surrounded on all sides by circular objects that resemble many black suns, symbols associated with Aryan cults and the upsurge of Nazism. In addition, a large sun-shaped disc can also be found at Wewelsburg Castle whose reconstruction was commissioned by head of the Gestapo, Heinrich Himmler. On March 31, 1945, a part of the castle was demolished on Himmler´s orders, the site became a symbol of destruction for several successive decades.

The Grandfather´s name, Josef K., may evoke associations with Kafka´s famous novel The Trial, whose bleak atmosphere is likewise reflected in Vičar´s diary entries from the time of his stay in Konstanz. Whereas Josef K. of the novel stood trial for a crime which was never specific to him and which he was unaware of having committed he eventually ended up executed. The present-day “Opa,” Josef K., volunteered for service in the largest-scale military conflict of the past century, has never felt the least remorse about his acts, and believes he will be granted a place in heaven after death.

Still, Jan Vičar refrains from passing any judgment

on the old man; rather, he remains more than anything else

a witness, a chronicler of the man´s life and family background, which he proceeds to transform into the metaphoric idiom of print maintaining links with his previous works. The figures in Vičar´s prints are copiously enshrouded in ornaments. The artist´s rendition reaches beyond the boundaries of printmaking, entering into the realm of painting, likewise in accord with his earlier output. Vičar´s practice is supported by the training he received as a student at the Prague Academy of Fine Arts, where his teachers were František Hodonský, head of the landscape painting studio, and subsequently Jiří Lindovský, head of the printmaking studio. He himself has achieved a symbiotic combination of the two media, somewhat ironically propelling printmaking, a method otherwise largely focused on smaller-scale formats, up to a monumental scale, with the use of, among other devices,

painting techniques.

Markéta Odehnalová, 2014

diary of Jan Vičar

In January 2012, I found myself virtually without money. My last previous royalties had paid for a new roof on my forest house. The first job offer I then chanced upon was for work as a skiing coach in the Giant Mountains. I quite enjoyed that short winter-season coaching career, notwithstanding the fact of my charges there being mostly rotund German ladies complaining of arthrosis, and small kids. The next offer was for a stint as a care provider in the German city of Konstanz. My arrival in Konstanz, in April 2012, set things in motion, and it was then that deep down in my thoughts I began to work on a new series of pictures. The diary entries in my sketchbook from there and then document the goings-on in that “family.”

— Jan Vičar, in the woods under Javořice hill, near Telč, 27. 04. 2014.

11/04 So Opa is an ex-SS police officer, as El told me. The first week took its course under the sign of his hatred. I was repeatedly addressed as gipsy, or devil, and one who´d best go back to the concentration camp. I complained to his daughter, El, saying that under such circumstances I wouldn´t carry on with my work.

El pleaded with me, tearfully, saying they had no one else and that I was doing my job well, that I should stay on. I agreed. El is not getting along too well with her husband. When they see each other in the evening, they don´t even say hello. They constantly blame each other for all kinds of things. These quarrels are usually interrupted by Opa hollering they ought to throw him out onto the street, that he no longer wants to live in this world. El keeps fretting around him, like a busy bee: a freshly baked croissant in the morning, then I prepare lunch. It always has to be freshly made, as yesterday´s leftovers are forbidden.

In the evening, I and C. (El´s husband) were hauled over the coals. Summoned by the big chief herself. We were like schoolboys before the headmistress. C.´s fault was having served Opa a stale fish (which wasn´t actually stale), and I for my part was getting used to leaving for a walk all too often. To that I retorted that I´d always asked for a leave and that I wasn´t used to staying in a place heated to 40 degrees centigrade. Everybody laughed at that, except El.

12/04 Today I got Opa into trouble: I gave him an Easter lamb cake for breakfast. Unfortunately, he choked on a bite and started to cough. I slapped him on the back. El accused me of having induced grandpa to cough. After the Easter lamb accident, El got hysterical and threw almost all foodstuffs out of the fridge. She said they were stale. In the evening there was yet another scene involving the toilet bowl I´d cleaned, as it was all pissed over by Opa. But I forgot to clear away the bucket of water with detergent I´d used in the cleaning. El instantly attacked me saying the cat would drink of it and die. To my objection that the cat would not drink chemically laced water on its own accord, she showered me with ironic remarks.

13/04, morning El didn´t like my having left a sideboard half-open after clearing the table. Opa complained about his underpants being loose. Only later on, after the underpants were safely hung on the washing line, El found out the elastic waistband had snapped. She started to curse, lamenting thirty euros having gone down the drain. To that I replied that she was free to detract it from my pay, that I hadn´t noticed. El told me I wasn´t the right person for the job, being unable to find out about a snapped waistband. I remarked I hadn´t bitten the waistband off, and that I´d gladly leave if she wished me to.

13/04 The evening once again brought something unexpected. El rolled in a while after six o´clock, and raised havoc about Opa not having had enough to drink. He was supposed to down three large glasses in the morning, and another four in the afternoon. I had conscientiously marked down the finished glasses. He wouldn´t have the liquid forced down his throat, so there hadn´t been enough glasses. As a result of her abuse, I´m going to mark down even unfinished glasses the next time out. El got lost somewhere, and grandpa began to sweat awfully hard. So I switched off the lights above his head that serve to keep his head warm. His son, S., became useful as a source of information for the first time. Then I unbuttoned Opa´s shirt and flapped it around, thereby fanning him. El rolled back in and started to shout at me that he´d catch a chill, etc. The room temperature is constantly 40 degrees centigrade. She went on to shriek about other things. Also about my having served Opa the Easter lamb cake, and about all men being buggers. I retorted that I´d already heard that, that she´d already said so last night. Today I fretted around from 6 a.m. till 4 p.m., then spent a while drawing Opa in his sleep. Again, S. spilled the beans on me. He´s a little swine. The situation reached its climax at breakfast. C. did a poor job of cutting up grandpa´s sausage, wherefore El flushed it down the sink. She cut it up again, herself. At 10 p.m. I went out for a stroll, I´m not allowed to stay out later than 11 p.m. This is my only time of peace during the whole day. In the course of that hour I smoke about five cigarettes, taking a night-time walk along the neighbourhood gardens. After my return the situation once again exacerbated, ending up in another bout of screaming. There´s something wrong with Opa´s eye, and I´m to blame for it. Arschloch – asshole – happens to be the most frequented word I hear. Around 11.30 p.m. I went to bed. I still hear the hollering at 1:30 a.m.

14/04, morning Shouting again: this time it´s my having left the detergent on the sink board after washing up. I did leave it there, as I hadn´t yet been finished with the work. She hurled the bottle under the sink, snapping about how many times she´d yet have to put it in its proper place. The beef I´d cooked with sauce yesterday, ended up discarded in the dustbin.

Only this evening, after nearly a week, did I learn that living together with us in the flat were also two dogs. Now I know why I´m not allowed to set foot in their apartment. What a scene it must be! I haven´t yet seen the dogs ever being walked. They are mongrels, but pretty aggressive too. They bared their teeth at me straight away, and one scratched me with its claws. There´s been some blood, as owing to the heat I always wear shorts. The nicest of them all though is Romeo the cat, whom I pamper now and then with a bit of something or other from the fridge. He´s my red-haired mate.

15/04 El rolled in at 9.15 p.m. We all waited for her to get Opa´s plate ready. I no longer recall why she did so, but she snatched her own plate with her favourite mayonnaise salad, and disappeared in her flat. She came back around 10 p.m., at a time I was going to take my hour-long stroll. El started to beseech me not to go anywhere, as they were having a visitor in the next-door flat, Mr B. (the landlord), who might bump into me and see me. I replied that I was properly dressed (though I was usually referred to as the dirty pig), and I was completely at a loss to see why Mr B. couldn´t see me. Her husband, C., was equally baffled. She then proceeded to grumble under her breath, so B. wouldn´t hear. She used the word, Tschechei. I explained to her that this was a pejorative label for my home country, which had originated in the Third Reich. Shouts again, this time at full throttle, calling me a Czech nationalist. She then grassed on me to Opa, telling him I was an alcoholic since I drank wine. Were she to know I have a bottle of slivovitz stashed away in the car! I pour myself a drink every time before a walk, to calm myself down a bit. I went out without permission, and did not meet Mr B. As I didn´t have the key, I had to ring the doorbell. The beast was already there in the corridor, waiting for me.

She jumped up and down on the spot, her legs slightly spread, like a monkey, scratching her cunt. She accompanied her monkey jumps with rhythmic shouting, “That´s the only thing you´re good at, Czech pigs.”

I couldn´t help bursting out in laughter.

16/04 Sunday is my sole day off. I took a trip to Schaffhausen, Switzerland, to see some friends of mine. A couple of hours of peace and quiet, at long last. I had to be back by evening. C. was there to meet me, to unlock the parking lot gate. To my query of how they had been doing, he replied, “Bullshit, as ever.” I went up, and only with the lights on did I notice that Opa had a blue eye and C. was bruised on the neck. Eventually, it transpired that they´d had a fight at lunch. S. reportedly held Opa back, and El did the same to C., otherwise they´d have done each other in. That I can easily imagine. C., permanently mad with everyone else, can never say anything, let alone decide, set against the old Leningrad hand, Opa, constantly circled by his busy bee. An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth, and a blue eye for a bruise. In such situations, C. usually flashes into the Nazi salute, to drive Opa mad. I´ve gone through that several times by now.

17/04 The swine had arrived, and once again all was wrong. C. would usually get dinner ready, with my help. I´d waited till 8 p.m., and still nothing happened. So I kept waiting, until 8.30. Subsequently, they chastised me about not having done my job. I told them I would leave as soon as I got a chance, that I was fed up. The key, which they would usually leave in the inside keyhole of the door to the flat, was not there tonight. I am actually locked in. I can´t use the window, to rope down on a line made of torn bed sheets, as I pondered. The window is fitted with security bars. As I fall asleep, I can still hear fragments of ironic remarks about my life in the forest hut, on a diet of bacon flushed down by wine. I was also told that the screen on the window of the living room where Opa stays all day long, had to be drawn, as Mr B. (the landlord) didn´t like it to be lifted so everyone could peer inside. I can´t see how anyone could peek in, the flat being upstairs. I outraged her by remarking the place reminded me of a bunker. I still have to listen to ironic queries about whether I recall yesterday´s orders, and the like. She forbade me to walk out to the balcony, so I went there to light up. This evening, all is wrong again. Opa was going to throw a piss-soaked slip of paper he uses to wipe his dick on into the bowl on the john. It got stuck onto the rim of the bowl. Again, remarks about it being my job to discard the piss-soaked strips. Then I led Opa to bed. And once again, all was wrong. Opa could have bumped his head, only he didn´t. I was again reminded of the curtains having to remain drawn so nobody could peek in. At dinner, I did something wrong passing on water, or I used the wrong beer glass. Another reproach: the balcony door was not locked but just closed. I forgot about that. I must be going crazy. Perhaps that might be the real purpose of it all. Again, I left the bathroom door open at a time when the ceiling window was open, and Opa was ex-

posed to draft. In fact, it was she who had opened the window, and forgot to shut it. El told me I wasn´t free to go out for a walk until 10 p.m. By now I refuse to have all those mayonnaise salads with them for dinner. I told her I was going to my room, to shout me back when she needed something. She still managed to chide me about having eaten Opa´s lunch at midday. Actually I didn´t eat it, it was that he didn´t want it. Opa doesn´t like pasta with cheese sauce. What he really enjoys are the real heavy Czech-style meals, like pork with dumplings and cabbage.

18/04 The gestapo woman has a day off. In the morning she slipped a piece of paper underneath my door with a list of chores for me. She reproached me about not wiping the floor. I replied that nobody had told me how often I was supposed to do it, with what, etc. I´d always wiped the john and bathroom floors. She claimed I was lying, that C. had shown me the machine. I replied that he hadn´t, and so it went on and on. She dragged in a red hoover that comes with a water container. She tested my skill, if I was able to fit in the container in the right direction. She has no notion of most academics being totally unendowed with technical prowess. However, I stood the trial. The floor sweeper is a piece of trash, I´d have managed sooner with a bucket and floorcloth. I failed to hang Opa´s underpants on the line in his room, as I didn´t want to wake him. He was still asleep.

10.20 a.m. Opa got up on his own, saying he wanted to go to the john. So we set out, at a snail´s pace, doing 20 metres in 20 minutes. He is unable to walk. He uses crutches. I stand either behind him or in front of him, in case he should fall.

In the middle of our john walk, the swine rushed in shouting he wasn´t supposed to get up, that he´d get wrong medical test results, and that I was a liar. She screamed so hard that Opa got all confused and kept winking at me, as though signalling he knew what it was about. Then I had to listen to a catalogue of ironic remarks about whether I would know when the alarm clock peeped. As soon as it did, I was to remove the meat from the hotplate, as she had to do the cooking. I was known for burning everything. In fact, it did happen last Saturday. C. was doing the cooking, and he burnt the meal. I then stirred it a bit to avoid its getting burnt still further. Again, S. spilled the beans. The little swine.

Midday: the big swine rolled in; more screaming about my not having cleared away the hoover. I didn´t, since the floor was wet and I didn´t want to step on it. A problem with towels. Not until one week into my stay was I shown where his towels are and how they were to be changed. Once I forgot to do it. El lifted up his dick towel and put it against my face, I pushed her away. She asked whether I wanted to use it to wipe my face with, and told me to do my job properly, as for her part she wouldn´t wipe her face with the towel he used to rub his penis on. I told her that nor would I either by any means, and suggested a simpler way of changing towels. She worked herself up to an even greater rage as I added that I wouldn´t even know whether he had a penis at all, at least I´d seen none, or it might be so small it escaped notice. She was mad. I hadn´t given him the meal because he hadn´t wanted it, I pointed out, adding it was good for one´s health in the spring season to abstain from eating for two days. This instantly turned against me. She called me a shitbag. I put my coat on and went out for 15 minutes while they were having lunch. She forbade me to go out for my evening hour of walking. In the afternoon, the beast underwent a peculiar sort of transformation. She was all saccharine sweetness, smiling even at me.

19/04 This morning, everything still o.k. Hummmm.

3.30 p.m. the arrival of S. whereupon the gestapo called asking about how much Opa had drunk. Once again, I´m being called a pig. After breakfast, Opa talks about the village where he was born, and about his childhood. Not for the first time, he concludes by saying, “I wanted to be a general but the war was too short.” I choose not to comment, and turn on the telly showing the popular series, Richter Hold. That is likewise symbolic. Opa´s best-loved television hero is judge Alexander Hold.

20/04 In the morning there was a call from the agency telling me the gestapo woman wanted me to stay on still on 24th April. I replied in writing, saying I wanted 250 euros for that. The fat swine shouts me down again, calling me lazy pig. Right now Opa is calling out to El, from the john: “Du bist ein Schwein!” The insults continue to pile up, the situation rising up to a climax. Yet strangely, my nerves show a good deal of resilience, otherwise I´d already culled her as a pig. This is approximately how our conversation runs: “Vičááár, you filthy Czech pig, you´ve nothing to do?” “Becheeeer, I´ll go about it soon as you fuck off.” That´s for the morning. At last she´s off. By now though, it´s the old man hollering again, who´s supposed to get up on time for his blood pressure, sugar, acid and pulse to be measured. He wants to sleep on. Generously, I give the old Nazi wanker another ten minutes. He gets up, we drag on

to the john, I sometimes make a drawing of him on the way.

But I keep watch on him. First he washes, sometimes cleans his teeth, changes into day clothes. That´s something we do all the time, the changing. Opa sweats enormously, and so do all of us here. The afternoon sun does its best outside, and here the heating´s on to the max. As for Opa, he must have chilled down a bit at Leningrad at least. I pass him the hearing aid, he won´t have it either. While he does his washing, I sometimes observe his scarred back. That harks back to his term in the Czech camp. El had already managed to blame me for that. Then we start up for breakfast. Now and then, we talk while eating. Yesterday, however, Opa gave me a surprise. Evidently moved, with tears in his eyes, he intoned the Czech national anthem, in German naturally.

21/04 Morning, and shouting again, addressed to all. Then she got lost. I cleaned the table, did the washing, hoovered the place, and wiped the floors. I had breakfast. Then I wake Opa, take his blood pressure while he´s still calm, drop some shit into his eyes, measure acid and sugar levels. Everything´s within the norm. The old man can´t walk properly but otherwise has a pretty tough root. Yesterday she forbade me to give him his pills, as I was an irresponsible pig. Today either C. or S. are in charge of that. Only they aren´t here. The Nazi has to get his pills down his throat early on, still before breakfast. I give them to him. I know exactly how many of them and which ones. Opa does protest, saying she´d shout at me again, but what the hell. While cleaning his teeth, Opa notes: “Up in heaven nobody will ask me whether or not I cleaned my teeth.” That´s fascinating: he believes he will get to heaven. The swine called, asking whether C. or S. were in. They aren´t I reply. She sweetly asks me if I would dispense the pills. I reply that though I´m not responsible enough, I will. So C. and S. are in trouble, ha-ha-ha.

In the evening I get a fresh nickname. True, the pig has

by now became somewhat overused. I´m now called Scheisstip. Not to forget: it´s Scheisstip, as Opa puked. I told her I was leaving on Tuesday, as had been agreed, and if I wasn´t allowed I was going to see the police. She replied she´d tell the police I´d beaten Opa up, since he has bruises on his chest. These date from his fight with C. last week.

22/04 At last, freedom in Switzerland. First F. and I sat down to write a letter of complaint, then I drove on to Stein, where I met the Buddhist, Andy, my future employer. We went to dinner together, then I drove L. to Schaffhausen. In the evening, I had a conversation with the gestapo woman. She tried to restrain herself but she was bothersome all the same. She still wants me to pay for the angels from the nativity scene. The nativity scene was displayed well into April right under the drawn curtain which in fact I willingly raised on two occasions. That was because Opa wanted to see the outdoors, and I didn´t want to spend the day in darkness. The day before yesterday, by when the curtain was already definitively drawn, Opa and I were sitting in front of the telly watching judge Hold, and then all of a sudden, bang, and the whole curtain came down, falling on the nativity scene. Four angels got broken. Naive as I was, I glued them together, and told El about the accident. She instantly blamed me, as it was I who´d tampered with the curtain.

23/04 Monday. An invoice has been drawn up for 1,600 euros. I wonder what´s going to happen in the evening. Yesterday the Beast got a call from the agency.

Opa shouted at her on the phone that he felt like being

in the grave, and that he wanted the curtain to be raised. Then he started to twitch, protesting he´d raise it by himself. The gestapo woman shouted him down on the phone. Evening come, I was blamed for spilling Opa´s tablets and not letting him have them. This was owing to S.´s having scraped up a pill from under the bed. When I was about to leave (15 minutes earlier), she wouldn´t let me go, so I told her to get stuffed. As I was on my way, she tried to trump me saying she´d show the doctor how I mauled up Opa.

24/04 There´s a problem: a technician wants to come and see Mr K. about his ears, but the swine is not in. It´s up to me to turn him off. I wonder how this is going to end. Josef K.´s hearing aids are consistently inadequate, and this is already the fourth appointment for the technician who´s supposed to adjust it. In fact, I once unwittingly dropped one of the aids. A plastic piece got chipped off, so I may yet have to pay for it. Up till moving to Konstanz, Opa worked as an insurance agent in Schwarzwald. The Freiburg diocese.

Now the hearing-aids guy has arrived. Before, I changed Opa´s clothes, taking my time. Finally, she jumped up, took off his under-vest and hurled it into my face. So I hurled it back at her. She threatened me that if I hit her, that was it. I told her I wasn´t going to make her happy doing that. In the evening, she forbade me to go out, so out I went.

25/04, morning I may be needing a lawyer yet. The little Angeber (informer), S., has stayed at home, has a headache, poor little thing. I wanted to walk out to the balcony, to light up, then luckily had second thoughts on it. S. would promptly report it to the gestapo. The situation climaxes in the evening. Opa choked on a lump of his meal – at least El thought so. In fact, he just coughed. Still, I´m called shit. She found out I had been overactive and dried her blouse and jeans in the dryer. They´d probably shrunk as a result, so she wouldn´t be able to wear them again. In fact, though, she´d forgotten to take her things out of the dryer. It´s not my duty to look after her clothes, they just happened to be in the dryer, so I dried them putting on the temperature normally used for drying the general´s underpants. Now she´s shrieking like a shot sow. She´s all beside herself when I tell her that at least she has a valid reason now for slimming down. She kicks at the door and hurls out abuse. Says she´ll detract another 150 euros from my pay. She and Opa howl at each other in a monstrous way. They won´t let him be. I sit with them after dinner. The swine is at pains trying to find a new way of ridiculing me, so she sets about parodying the tune of the Vltava, by Bedřich Smetana. The very part where Smetana found a masterly way of recreating the gurgling voice of the river Vltava at its source. The swine emits a strange travesty of musical sounds, something in the manner of bloo– bloo– bloo–, lampooning the flow of water. I feel like spitting her in the face. At least I tell her that not everything is as deafening as Wagner. She once again unfolds her story about my mauling up Opa. I ask C: “C., you know how it happened with Opa, that it was you who beat him up.” He replies, “I no longer recall anything about that.” I ask him why he is staying on with this awful woman. For the first time, C. gives a hearty laugh. We squabble over money. They don´t want to pay me the Easter holiday wage, which is legally set at double the standard rate. They argue I didn´t do any work. I claim that I was at their disposal, and repeatedly inquired about work

to do. I recall that during the holidays they told me I could

go out for a walk, and the like. However, nobody explicitly told me I was off duty. My arguments turn out to be useless.

The evening brings a new quarrel; I refuse to communicate with her, and I no longer give a damn about Opa. I´m leaving tomorrow. She carries on shouting, kicking at my door. I open the door, trying to be polite, without really succeeding. She keeps cursing me, and I give as much as I get. I want to shut and lock the door. However, she has stuck her fat body into the doorway, a snoozing, sweaty beast obstructing the door frame, and now sticks up against my belly a sharp file. I slap her on the hand, she cries out and lets off the door. Finally, I´m able to lock it.

26/04 All is quiet in the morning, the swine being out. Only S. is at home, who is supposed to give me my pay. Detracted from the sum total of 1,600 euros are the angels, the blouse, and the jeans, plus repair of the hearing aid. The informer S. hands out to me 1,130.68 euros. I say goodbye to Opa and leave the flat. In the corridor I get a caressing brush-by from the cat, Romeo, my favourite member of the menagerie, whom I was forbidden to stroke. I pass by a photograph of El and S., smiling. I feel an urge to spit on the portrait, but I hold it back.

I still pay a short call at the consulting room of the doctor, which is in the same house. I twice met her in “our” place.

Our conversation runs roughly like this:

Jan V.: “Good morning, doctor, may I talk to you?”

Dr O.: “Yes, what can I do for you?”

Jan V.: “I worked here in this house, at Mrs El´s, as a health-care assistant. Mrs El told me she had a paper from you concerning bruises on the body of Josef K. El actually accused me of having beaten up Josef K.”

Dr. O.: “I have seen you several times, and I know you´ve worked at Mrs. El´s. We know about that family, and we´ve been following the goings-on there. You don´t make the impression on me of a person capable of beating up a helpless old man. I am confident you haven´t done it.”

Jan V.: “Thank you.”

Dr. O.: “You´re welcome. Have a nice journey.”

Almost exactly two years from the day I was taking leave

of Josef K. and his family, here I am copying down my Konstanz diary. Who were those strange people? The husband, C., a coward and a pathetic type who was happy to be able to leave home for work and spend a few hours without seeing El. An individual who was only rarely given the chance to say anything. A man who would look me in the eyes and lie, saying I´d beaten up General Josef K.

The grandson, S., didn´t need more than one month to become the busiest informer in Konstanz.

My strongest memories, though, are those of El, her who

hated everyone around. I keep in my mind a vivid recollection of her, in her loose pale-green housewife garment, sweating profusely in the heat, her huge breasts drooping as she bends over a pot with a piece of black pudding or baked pork for Opa. The fume hood that was never on, the windows that were seldom open, the heavy air, the sultry heat, and the constant flow of abuse – those are my lasting memories of that family.

Josef K.´s unfulfilled dreams, his nostalgic memories of

the Sudeten of his childhood, the ethnically mixed Czech-German village where he grew up and played his children´s games, and where he also witnessed the first military parades, the siege of Leningrad, and the subsequent internment in the Czech concentration camp in Česká Kamenice; all of that came to be projected into my mind during a single month of 2012. I can still see the sorry figure of this would-be general, still recall his yearning. The man who was moved to tears by the sight on the tv screen of German soldiers marching past in a Second World War documentary.

I was glad then to be leaving that strange, dark house where curtains had to be kept drawn.

I recall it was a sunny day, and I was on my way to the south, to Switzerland, to a Buddhist community, to work on the construction of their house. But then, that´s already another story.

— in the woods under Javořice hill, near Telč, 27. 04. 2014.

Ich wollte General werden, aber der Krieg war zu kurz.

Diese Worte sagt in Jan Vičars Tagebuch „Opa“ Josef K.,

ein ehemaliger Angehöriger der SS-Polizei-Division, der heute mit seiner Tochter in Konstanz am Bodensee lebt. Jan Vičar kümmerte sich um ihn im April 2012

als Betreuer.

Von seinem Aufenthalt in Deutschland brachte der Künstler nicht nur Erlebnisse mit nach Hause, sondern auch ein Tagebuch mit Eintragungen und Skizzen, die er in sein Werk einfließen ließ – monumentale Linolschnitte, inspiriert vom Leben des Josef K. Die entstandenen Linolschnitte sind voller Metaphern und nehmen auch Bezug auf Vičars ältere Arbeiten. Der Druck Chlapec s obrazem (Junge mit Bild) ist vom slowakischen Volkslied Pasol Jano tri voly (Jano hütete drei Ochsen) inspiriert. Die Hauptgestalt ist hier ein Junge mit einer Trommel, der auf das Bild des sterbenden Jano schaut.

Die Trommel, das Symbol für das Soldatenspielen kleiner Kinder, begleitet den Jungen auch auf zwei weiteren großformatigen Linolschnitten: in den Bildern Houpačka (Die Schaukel) und Bubeník (Der Trommler). Die Schaukel lässt den Jungen Raum und Zeit vergessen, ermöglicht ihm einen Übergang vom festen Boden ins Leere und zugleich einen Sprung ins Wasser unter sich. Das Motiv des Übergangs von einer Welt in eine andere entfaltet sich dann zur Gänze im Bild Převozníci (Hotel Melencolia) (Die Fährmänner (Hotel Melencolia)).

Für die Fährmänner ließ sich Vičar von Dürers Stich Melencolia I inspirieren, der mittels verschiedener Zeichen und Ziffern auf den Planeten Saturn als ein Symbol für den Lauf der Zeit, für den Tod und die Vergänglichkeit verweist. Auf Vičars Blatt ist eine Leiter abgebildet, die auch bei Dürer nicht fehlt. Es könnte Jakobs Leiter sein, eine Verbindung zwischen Himmel und Erde, ein Kontakt zu Gott und der Weg, über den in Jakobs Traum die Engel auf- und niederstiegen. Von der Spitze der Leiter sprach auch der Herr zu Jakob. Die Fährmänner sind von allen Seiten von runden Körpern umgeben, die an schwarze Sonnen erinnern, welche auf Arierkulte und den Aufstieg des Nationalsozialismus verweisen könnten.

Eine große Sonnenscheibe befindet sich jedoch auch auf

der Wewelsburg, die Gestapo-Chef Heinrich Himmler umbauen ließ. Am 31.3.1945 wurde ein Teil der Burg auf Himmlers Befehl hin zerstört, und die Wewelsburg wurde für mehrere Jahrzehnte zum Symbol des Verfalls. „Opas“ Name Josef K. kann Assoziationen mit Kafkas berühmtem Roman Der Process wecken, dessen drückende Atmosphäre auch Vičars Aufzeichnungen aus Konstanz ausstrahlen. Während der Romanheld Josef K. für ein Verbrechen vor Gericht steht, worüber ihm niemand Auskunft geben kann und dessen er sich nicht bewusst ist, für das er jedoch letztlich hingerichtet wird, nahm der zeitgenössische „Opa“ Josef K. freiwillig am größten militärischen Konflikt des vergangenen Jahrhunderts teil, ohne sein Handeln je bereut zu haben, und in der Überzeugung, dass ihm nach dem Tode ein Platz im Himmel bestimmt ist.

Jan Vičar verurteilt den Alten jedoch nicht; er wirkt eher wie ein Zeuge, ein Chronist seines Lebens und seiner Familienverhältnisse, die er in grafische Metaphern transformiert, die wiederum an seine vorherigen Arbeiten anschließen. Die Figuren auf Vičars Drucken sind reich mit Ornamenten versehen. Der bildnerische Ausdruck des Künstlers überschreitet die Grenzen der Grafik und geht, wie auch in seinem früheren Schaffen, in den Bereich der Malerei über. Vičars Praxis geht von seinen in der Studienzeit erworbenen Fertigkeiten aus, als er an der Akademie der bildenden Künste ein Schüler František Hodonskýs und dessen Atelier für Landschaftsmalerei war und in der Folge auch das Atelier für Grafik von Jiří Lindovský besuchte. Beide Medien vermag er daher zu verbinden, und die Grafik, die meist in kleinen Formaten zum Ausdruck kommt, paradoxerweise zu monumentalisieren, auch mit den Techniken der Malerei.

Markéta Odehnalová, 2014

Tagebuch von Jan Vičar

Im Jahr 2012 war ich so gut wie ohne finanzielle Mittel.

Für mein letztes Honorar kaufte ich ein neues Dach für mein Waldhaus. Die erste Arbeit, die mir damals angeboten wurde, war die eines Skilehrers im Riesengebirge. Ich mochte diese kurze Winterkarriere, obwohl ich mich um korpulente, arthrosegeplagte Damen aus Deutschland und kleine Kinder kümmern musste. Eine weitere Gelegenheit bot sich als Betreuer eines alten Mannes in Konstanz am Bodensee.

Mit meiner Ankunft in Konstanz im April 2012 begannen sich die Dinge zu entwickeln und ich begann, in Gedanken an einem neuen Bilderzyklus zu arbeiten.

In einem Notizblock habe ich in täglichen Aufzeichnungen festgehalten, was alles in dieser „Familie“ passierte.

— Jan Vičar, im Wald am Berg Javořice nahe Telč am, 27. 4. 2014

11. 4. Opa ist also ehemaliges Mitglied der SS–Polizei-Division, wie mir El. erzählte. Die erste Wochestand im Zeichen seines Hasses. Ich wurde wiederholt als Zigeuner und Teufel bezeichnet, der ins Konzentrationslager zurückkehren solle. Ich sagte seiner Tochter El., dass ich unter den gegebenen Umständen

die Arbeit nicht fortsetzen werde.

El. bat mich und weinte, dass sie niemanden haben und dass ich alles gut machen werde und bleiben solle. Ich willigte ein.

El. hat keine gute Beziehung zu ihrem Mann. Abends, wenn sie sich sehen, grüßen sie einander nicht. Die beiden werfen sich unentwegt etwas vor. Und dann fängt in der Regel Opa an zu brüllen, dass sie ihn rauswerfen sollten, dass er nicht mehr auf der Erde sein wolle. El. tut alles für ihn wie die fleißige Biene Maja, morgens stets ein frisches Croissant. Ich koche dann Mittagessen, immer frisch, da kein Essen vom Vortag auf den Tisch

kommen darf.

Heute Abend musste ich mit Ch. (dem Ehemann von El.) antreten. Die Chefin hatte uns gerufen. Wir standen vor ihr wie Schüler vor der Lehrerin. Ch. soll Opa einen alten Fisch gegeben haben (der Fisch war nicht alt), und ich würde zu oft spazieren gehen. Ich antwortete, dass ich es mir erlaubt habe und ich nicht an 40 Grad Hitze gewöhnt sei. Alle lachten darüber, außer El.

12. 4. Heute habe ich Opa ein Stück vom Osterlamm zum Frühstück gegeben. Leider verschluckte er sich und begann zu husten. Ich schlug ihm daraufhin auf den Rücken. El. beschuldigte mich, dass ich Opa den Husten verursacht habe. Nach dem Vorfall mit dem Ostergebäck warf El. hysterisch alle Lebensmittel aus dem Kühlschrank, weil sie zu alt seien.

Abends machte El. noch eine Szene wegen der Toilette, die ich gewischt hatte, da Opa daneben gepinkelt hatte. Ich hatte das Wasser mit dem Reinigungsmittel, mit dem ich die Toilette geputzt hatte, stehen lassen. El. fuhr mich sofort an, dass der Kater daraus trinken und verrecken werde. Auf meinen Kommentar hin, dass der Kater von sich aus keine Chemie anrühren würde, musste ich mir ironische Bemerkungen anhören.

13. 4. morgens El. missfiel, dass ich nach dem Saubermachen einen Schrank halb offen gelassen hatte. Opa beschwerte sich, dass ihm die Unterhosen rutschen. Erst als sie auf der Leine hingen, stellte El. fest, dass der Gummi gerissen war. Sie begann zu fluchen, dass dreißig Euro futsch seien. Ich sagte ihr, sie könne es mir vom Lohn abziehen, weil ich es nicht bemerkt habe. El. sagte, ich solle diese Arbeit nicht machen, wenn ich einen kaputten Gummi nicht bemerken würde. Ich antwortete, dass ich den Gummi nicht durchgebissen habe und gerne mit der Arbeit aufhöre, wenn sie dies wünsche.

13. 4. abends Wieder etwas, was ich nicht erwartet habe. El. kam nach sechs Uhr und machte Krawall, weil Opa zu wenig getrunken habe. Er soll drei große Gläser vormittags und vier nachmittags trinken. Ich machte Striche für ausgetrunkene Gläser. Aber er wollte nicht trinken und ich konnte ihn nicht zwingen, sodass es letztlich zu wenige Gläser waren. Für ihr Geschrei werde ich nun Striche auch für nicht ausgetrunkene Gläser machen. El. verschwand irgendwohin und Opa begann schrecklich zu schwitzen. Ich löschte also die Lampe über ihm, die ihm auf den Kopf strahlte. S., der Sohn, erwies sich zum ersten Mal als Petze. Ich machte Opa das Hemd auf und begann ihm Luft zuzufächeln. El. kam hinzu und fing an zu schreien, dass er auskühlen werde etc. Wir haben immer noch 40 Grad Celsius. Sie fing an über andere Sachen zu schimpfen. Darüber, dass ich Opa diesen Osterkuchen gegeben hatte, und dass alle Kerle Scheiße seien. Ich sagte daraufhin, dass ich dies bereits in der Nacht von ihr gehört habe. Heute arbeitete ich von 6.00 bis 16.00 Uhr, und zeichnete dann ein wenig Opa, wie er schlief. S. erzählte es wieder weiter, der kleine Dreckskerl. Zum Frühstück spitzte sich die Lage zu. Ch. hatte dem Großvater die Wurst schlecht abgeschnitten und El. warf sie daher ins Spülbecken. Ich schnitt ihm dann Wurst ab. Um 22.00 Uhr ging ich spazieren, länger als bis 23.00 Uhr ist es mir nicht erlaubt. Es ist die einzige ruhige Stunde am Tag. Ich rauche in dieser einen Stunde ca. fünf Zigaretten und laufe zwischen den Gärten durch die Nacht. Nach meiner Rückkehr erwartete mich erneut Geschrei. Opa hatte etwas mit dem Auge und es war meine Schuld. Arschloch ist das Wort, das ich am häufigsten höre. Gegen 23.30 Uhr gehe ich schlafen. Noch um 1.30 Uhr nachts höre

ich Gezeter.

14. 4. morgens Wieder Gebrüll. Dieses Mal hatte ich beim Saubermachen das Spülmittel auf der Küchenzeile vergessen. Ich hatte es stehen lassen, weil die Arbeit noch nicht fertig war. Sie schleuderte das Geschirr unter das Spülbecken mit den Worten, wie oft sie das hier denn noch aufräumen müsse. Der Rinderbraten mit Soße, den ich abends gekocht hatte, war im Abfalleimer.

Abends, erst nach einer Woche, erfuhr ich, dass mit uns hier noch zwei Hunde leben. Ich verstehe, warum ich nicht einen Schritt in ihre Wohnung darf. Ich stelle mir vor, wie es dort aussehen muss – ich habe noch nicht gesehen, dass jemand mit den Hunden spazieren gegangen ist. Es sind Mischlinge, aber von aggressivem Naturell. Sie begannen gleich die Zähne zu fletschen, einer kratzte mich mit seinen Krallen. Es blutete ein wenig, weil ich wegen der Hitze kurze Hosen trage. Am liebsten ist mir aber Kater Romeo, ich füttere ihn manchmal mit Sachen aus dem Kühlschrank. Mein rostfarbener Freund.

15. 4. El. kam um 21.15 Uhr. Alle warteten, dass sie Opa den Teller fertig machen werde. Ich weiß nicht mehr warum, aber sie packte ihren Teller mit Mayonnaisesalaten voll und verschwand in ihrer Wohnung. Sie kam gegen 22.00 Uhr zurück, als ich auf meinen abendlichen Rundgang gehen wollte. El. bat mich nachdrücklich, nirgends hinzugehen, da Herr B. (der Hausbesitzer) in der Nachbarwohnung zu Besuch sei und er mich sehen könne. Ich sagte, dass ich sauber angezogen sei (auch wenn ich als Dreckschwein bezeichnet werde) und ich nicht verstehe, warum Herr B. mich nicht sehen dürfe. Auch ihr Ehemann, Ch., wunderte sich. Sie begann leise zu schimpfen, damit B. es nicht hören konnte. Sie benutzte den Begriff Tschechei. Ich erklärte ihr, dass dies eine abwertende Bezeichnung für mein Heimatland sei und ihren Ursprung im Dritten Reich habe. Sie schrie erneut, diesmal laut, dass ich ein tschechischer Nationalist sei. Opa erzählte sie dann, ich sei Alkoholiker, weil ich Bier trinke. Sie weiß nicht, dass ich eine Flasche Sliwowitz im Auto habe. Immer vor dem Spaziergang trinke ich einen Schluck, um ruhiger zu werden. Ich ging ohne Erlaubnis raus und habe Herrn B. nicht getroffen. Da ich keinen Schlüssel hatte, musste ich klingeln. Die Bestie wartete auf dem

Gang auf mich.

Sie sprang wie ein Affe mit leicht auseinandergezogenen Beinen und kratze sich dabei an der Möse. Im Rhythmus der Affensprünge brüllte sie: „Was anderes könnt ihr nicht, ihr tschechischen Schweine.“

Ich musste laut loslachen.

16. 4. Sonntag ist mein einziger freier Tag. Ich fuhr in die Schweiz, nach Schaffhausen, zu Freunden. Endlich ein paar Stunden Ruhe. Am Abend musste ich zurückkehren. Ch. öffnete mir das Tor am Parkplatz. Auf meine Frage, wie der Tag war, antwortete er: „Scheiße, wie immer.“ Ich kam nach oben und erst im Licht sah ich, dass Opa einen blauen Fleck unter dem Auge hatte und Ch. einen am Hals. Sie rückten damit heraus, dass sie sich beim Mittagessen geprügelt hatten. S. hielt angeblich Opa und El. hielt Ch., weil sie sich sonst umgebracht hätten. Ich kann es mir gut vorstellen. Ch., permanent wütend auf alle, der nie etwas sagt und sich nie entscheiden kann, und der Opa, der alte Schütze vor Leningrad, um den die fleißige Biene Maja schwirrt. Auge um Auge, Zahn um Zahn, blauer Fleck um blauen Fleck. Ch. fängt in solchen Momenten meist an Heil Hitler zu rufen, um Opa zu ärgern. Das habe ich mehr als

einmal erlebt.

17. 4. Die Fuchtel kam und wieder war alles schlecht. Das Abendessen bereitete meist Ch. mit meiner Hilfe zu. Ich wartete bis 20.00 Uhr und nichts passierte. Also wartete ich bis 20.30 Uhr, bis sie mir vorwarfen, dass ich das Abendessen hätte machen sollen. Ich sagte ihnen, dass ich bei der ersten Gelegenheit gehen werde, dass ich die Nase voll habe. Der Schlüssel, der sonst von innen in der Tür steckte, fehlte in dieser Nacht. Ich war de facto eingeschlossen. Das Fenster konnte ich nicht benutzen, mich am Bettlaken abzuseilen war nicht möglich. Es sind Gitter am Fenster. Beim Einschlafen hörte ich noch boshafte Bemerkungen, dass ich in der Hütte im Wald, wo ich wohne, nur Speck esse und Wein dazu trinke. Mir wurde gesagt, dass das Fensterrollo im Wohnzimmer,

wo Opa den ganzen Tag verbringt, heruntergelassen sein muss, da Herr B. (der Hausbesitzer) es nicht möge, wenn es oben ist und man hineinschauen kann. Ich verstehe nicht, wie jemand in die Wohnung schauen könnte, da sie im ersten Stock ist. Ich machte sie mit meiner Bemerkung, dass es hier wie in einem Bunker sei wütend. Sie sagte spöttisch, ob ich mich an Sachen von gestern erinnern könne etc. Sie verbot mir auf den Balkon zu gehen, ich ging zum Rauchen auf den Balkon. Der Abend verlief weiter schlecht. Opa warf ein vollgepinkeltes Stück Klopapier, mit dem er sich den Schwanz abgewischt hatte,

in die Toilette. Das Papier fiel auf den Rand. Und wieder musste ich mir anhören, dass es meine Arbeit sei, vollgepinkeltes Papier wegzuräumen. Dann brachte ich Opa ins Bett. Und wieder alles falsch. Opa hätte sich am Kopf stoßen können, stieß sich aber nicht. Mir wurde erneut erklärt, dass die Rollos unten sein müssen, damit man nicht hinein schauen kann. Beim Abendessen habe ich das Wasser falsch gereicht oder ich habe ein falsches Bierglas genommen. Und wieder Vorwürfe – die Balkontür war nicht verriegelt, sie war nur zugeworfen. Ich hatte es vergessen. Ich werde langsam wahnsinnig. Das ist wahrscheinlich der Sinn des Ganzen. Ich habe die Badezimmertür offen stehen lassen, obwohl das Deckenfenster offen war und es Opa zog. Das Fenster hatte sie aufgemacht und vergessen, es zu schließen. El. sagte mir, ich könne erst ab 22.00 Uhr spazieren gehen. Ich weigerte mich mit ihnen zu Abend zu essen. Mayonnaisesalate aller Art. Ich sagte ihnen, ich würde in mein Zimmer gehen und sie solle rufen, wenn sie etwas braucht. Sie fuhr mich noch an, dass ich mittags Opa das Mittagessen weggegessen habe. Das Essen hatte ich nicht angerührt, und er wollte es nicht. Opa isst keine Nudeln in Käsesoße. Er mag nämlich gute böhmische Küche: Knödel mit Schweinsbraten und Sauerkraut.

18. 4. Die Gestapo-Aufseherin hat frei. Morgens hat sie mir einen Zettel mit Aufgaben für den Tag unter der Tür durchgeschoben. Sie warf mir vor, dass ich den Fußboden nicht wische. Ich antwortete, mir hätte niemand gesagt wie oft und womit usw. WC und Bad habe ich immer geputzt. Sie sagte, ich lüge, Ch. habe mir das Gerät gezeigt. Ich verneinte dies. So ging es die ganze Zeit. Sie holte einen roten Wasserstaubsauger, in den ein Einsatz mit Wasser gegeben wird. Sie prüfte, ob ich es zustande bringen werde, den Wasserfilter in die richtige Position einzusetzen. Sie glaubt zu wissen, dass die meisten Akademiker technisch absolut unbeschlagen sind. Ich bestand den Test. Der Staubsauger ist völlig überflüssig, mit Wischlappen und Eimer wäre ich schneller fertig. Opa wollte ich seine Unterhosen nicht in sein Zimmer hängen, da er noch schlief.

Um 10.20 Uhr stand Opa von selbst auf und wollte aufs Klo. Und so gingen wir im Schneckentempo 20 Meter in 20 Minuten. Er kann nicht gehen. Er hat Krücken. Ich stehe vor ihm oder hinter ihm, damit er nicht hinfällt. Während unseres Klogangs kam sie angeschossen und bellte, dass er nicht hätte aufstehen sollen, dass er schlechte Messwerte haben werde und dass ich ein Lügner sei. Sie bellte in einer Weise, dass Opa nervös wurde. Aber er zwinkerte mir zu, als ob er wüsste, was hier vor sich geht. Dann musste ich mir eine Bemerkungen darüber anhören, ob ich erkennen würde, wenn ein Wecker klingelt. Sobald er klingelt, solle ich das Fleisch abstellen, weil sie ja kochen muss. Ich brenne ja alles an. Das war am vergangenen Samstag. Ch. kochte und ließ das Essen anbrennen. Ich versuchte noch so gut es ging etwas zu retten. S. hat es wieder sofort weiter erzählt, der kleine Dreckskerl.

Mittags – die Aufseherin rollte heran und bellte, ich hätte das Sauggerät nicht weggeräumt. Ich hatte es stehen lassen, weil der Boden noch nass war und ich nicht darüber gehen wollte. Ein Problem mit den Handtüchern. Erst nach einer Woche wurde mir erklärt, wo Opas Handtücher sind und wie sie ausgetauscht werden. Einmal hatte ich es vergessen. El. nahm das Handtuch für Opas Schwanz und drückte es mir ins Gesicht, ich drückte sie weg. Ob ich mir damit das Gesicht abwischen wolle, ich solle es ordentlich machen, weil ein Handtuch, mit dem er sich den Penis abwischt, sie nicht verwenden würde. Ich antwortete, dass ich dies sicherlich auch nicht tun werde und schlug ein einfacheres System des Handtuchwechsels vor. Sie tobte noch mehr, als ich sagte, ich wisse nicht, ob er einen Penis hat, ich habe keinen gesehen oder er ist so klein, dass er nicht zu sehen ist. Sie tobte. Ich gab Opa kein Essen, da er keines wollte. Ich fügte hinzu, dass es gesund sei, im Frühjahr zwei Tage zu fasten. Das wurde sofort gegen mich verwendet. Sie nannte mich einen Scheißer. Ich zog mich an und ging während ihres Mittagessens für 15 Minuten raus. Sie verbot mir meinen abendlichen Spaziergang. Nachmittags veränderte sich die Bestie. Sie war freundlich, sie lachte, sogar

mir entgegen.

19. 4. Heute Morgen ist alles in Ordnung O.K. Hmmm.

Um 15.30 Uhr kam S. und sofort rief die Gestapo an, wie viel Opa getrunken habe. Ich wurde wieder als Schwein bezeichnet. Nach dem Frühstück erzählte Opa über das Dorf, in dem er geboren wurde, über seine Kindheit. Wie schon mehrmals zuvor beendete er das Gespräch mit den Worten: „Ich wollte General werden, aber der Krieg war zu kurz.“ Ich fügte lieber nichts hinzu und schaltete den Fernseher ein, es lief seine Lieblingsserie, Richter Hold. Wie symbolisch. Opas TV-Liebling ist Richter

Alexander Hold.

20. 4. Morgens rief die Agentur an — die Gestapo–Aufseherin wünschte, dass ich bis zum 24.4. bleibe. Ich antwortete, dass ich dafür 250 Euro wolle. Die fette Sau brüllt erneut, dass ich ein faules Schwein sei. Jetzt brüllte Opa vom Klo aus El. an: „Du bist ein Schwein.“ Die Beschimpfungen gingen weiter, die Situation spitzte sich zu. Ich hatte seltsamerweise gute Nerven, sonst hätte ich ihr … Unsere Konversation verläuft in etwa so: „Vičááár, du stinkendes Tschechenschwein, hast du nichts zu tun?“ „Bechéééér, ich mache das, wenn Sie weg sind.“ Was für ein Morgen. Endlich verschwand sie. Jetzt brüllt aber der Alte, der wegen der Messungen von Blutdruck, Zucker, Säure und Puls zu genau bestimmten Zeiten aufstehen soll. Er will noch schlafen. Ich gebe dem Nazi großzügig 10 Minuten. Er steht auf, wir schlurfen zum Klo, auf dem Weg dorthin

zeichne ich ihn noch. Ich passe aber auf ihn auf. Zuerst wäscht er sich, manchmal putzt er sich die Zähne, zieht sich um. Umziehen ist eigentlich immer an der Tagesordnung. Opa schwitzt enorm, wie wir alle. Draußen brennt die Sonne und hier wird voll geheizt. Opa hatte ja diese Erfrierungen vor Leningrad. Ich gebe ihm sein Hörgerät, er will es nicht. Beim Waschen sehe ich manchmal die Narben auf seinem Rücken. Die hat er aus dem tschechischen Konzentrationslager. El. hat mir schon vorgeworfen, dass dies meine Schuld sei. Dann geht es zum Frühstück. Gestern hat Opa mich dann doch überrascht: ergriffen und mit Tränen in den Augen sang er die tschechische Hymne, selbstverständlich in Deutsch.

21. 4. Morgens wieder Gebrüll. Dann verschwand sie. Ich räumte das Geschirr weg, wusch Wäsche, saugte, wischte den Fußboden und frühstückte. Danach weckte ich Opa, maß den Blutdruck noch in Ruhe, gab ihm Tropfen in die Augen, maß den Säurespiegel und den Zucker. Alles normal. Er kann zwar nicht gehen, aber er ist zäh. Gestern hatte sie mir verboten, ihm Tabletten zu geben, weil ich ein verantwortungsloses Schwein sei. Heute obliegt dies Ch. oder S., die aber nicht hier sind. Die Tabletten müssen rechtzeitig noch vor dem Frühstück in den Nazibauch. Ich gebe sie ihm. Ich weiß genau wie viel und welche. Opa protestiert zwar, aber egal. Beim Reinigen der Zähne betont Opa: „Im Himmel wird mich keiner danach fragen, ob ich Zähne geputzt habe oder nicht.“ Es ist faszinierend, er denkt, er käme in den Himmel. Die Aufseherin ruft an, ob Ch. oder S. da seien. Ich verneine. Sie fragt freundlich, ob ich die Tabletten geben könne. Ich antworte, es sei zwar nicht meine Aufgabe, aber ich würde sie ihm geben. Ch. und S. haben ein ernstes Problem, hahaha.